“What mental health needs is more sunlight, more candour, and more

unashamed conversations.”

-Glenn Close

Our schools teach us everything, except Mental Health. Although on paper, we have policies and guidelines outlining its importance, it is hardly implemented in Indian school settings. The primary step towards addressing mental health education in schools must be psychoeducation regarding the existing laws and policies on the same. Recently, the National Education policy (NEP), has much to tell about this. Only at two places in the whole document is “mental-health” mentioned. First is where they require addressing mental health (given in brackets, next to health) to address foundational literacy and numeracy which is a requirement for learning. In the second place, it is mentioned under curriculum, where its mentioned that basic training in health, mental health, good nutrition, hygiene, etc. must be addressed. It touches upon addressing dire consequences of alcohol, and drugs. Hence, the importance of addressing addiction in school is stated. But this addiction is limited to substance only. NEP also takes a step forward in requiring mental health to be addressed in the curriculum, but how, through whom is very ambiguous, and not explicitly mentioned.

NEP requires counsellors/social workers to work on reducing drop outs and increasing gross enrolment ratio. Counsellors/social workers are also required to play part in teachers’ welfare, acting as a bridge to connect major stakeholders of school. With respect to inclusive education, it is their role to include economically disadvantaged group, improving their attendance and learning outcomes of all children. Counsellors/social workers will also play a role in transition from school to higher education, survey adults interested in learning, and connect them to adult education centres. But is the role of psychologists restricted to this? Primary prevention shall be the main focus, which is mentioned nowhere in NEP. Reducing mental-health stigma, increasing help seeking behavior, psychoeducation about mental health is not addressed at all. NEP isn’t able to distinguish between psychologists and social workers, everywhere they are mentioning the two together. Qualifications required for these counsellors too is unclear. The idea and role of psychology and psychologists too is clearly lacking.

Although NEP has been in the talks, but not much about MANODARPAN is known. MANODARPAN is an initiative by the Union Human Resource Development Ministry (MHRD), to provide psychosocial support to students for their mental health and wellbeing. It provides a website, a national toll-free number, directory of counsellors, to extend support to those requiring it. It has also published two books-21st century life skills, and Mental health and Wellbeing. It plans on introducing a chat based online platform to extend its services to students to aid help-seeking behavior and make audiovisual materials on mental health and wellbeing more accessible. MANODARPAN is an excellent step forward, taken by MHRD, but is not without its limitations. Although it aligns with Bronfenbrenner’s idea of ecological system in viewing the child as a whole, there are couple of inadequacies it holds.

MANODARPAN is a part of Atma Nirbhar Bharat- a short term initiative, with a short-term goal. But what about its sustainability? Ways to make this help long-terms hasn’t been discussed at all. Hence, a concrete law or a policy is required to mandate mental-health education in schools to keep this initiative long-term.

Simply providing psychosocial support, means acting at the tertiary level of prevention. What India needs today is more primordial, primary and levels of interventions and preventions. Shashtri (2009), recommends including early identification of problems, prevention and intervention plans to promote student wellbeing. MANODARPAN does do this through its handouts and flyers, but the content it covers is highly generalized ignoring some very important aspects of mental health. When it comes to mental-health a very general approach might not work. We need tailor-made approaches, and age-appropriate modules. How topics like bullying, addiction or abuse would be explained to primary school children, must be very different from how it will be addressed with high school students, and this is missing in MANODARPAN. More detailed and specialized material must be created. Hence its sustainability in the long run again is highly questionable.

Another question regarding MANODARPAN is its reach, which is very poor. Not many people are aware of it, or use its resources. Government has laid down no plans or mechanisms of ensuring that most people are able to access it. Mental health education is most required in the rural setting, who would be unable to largely access its online materials.

Srinivasmurthy (1993) rightly said that, “policies pertaining to children in India has pointed out to the lack of clear focussed policy/policies on child mental health. According to him the uncoordinated efforts of the various sectors, changing goals and not having targets which are reality based to the Indian scene are the reasons for that.”

Apart from polices on children, if we look at policies on education like Sarva Shiksha

Abhiyan and Early Childhood Care and Education for example, they cater to children’s

educational and physical health needs. But there are no comprehensive programmes to address the psychological issues of children (Ramalingam & Nath, 2012) except for MANODARPAN.

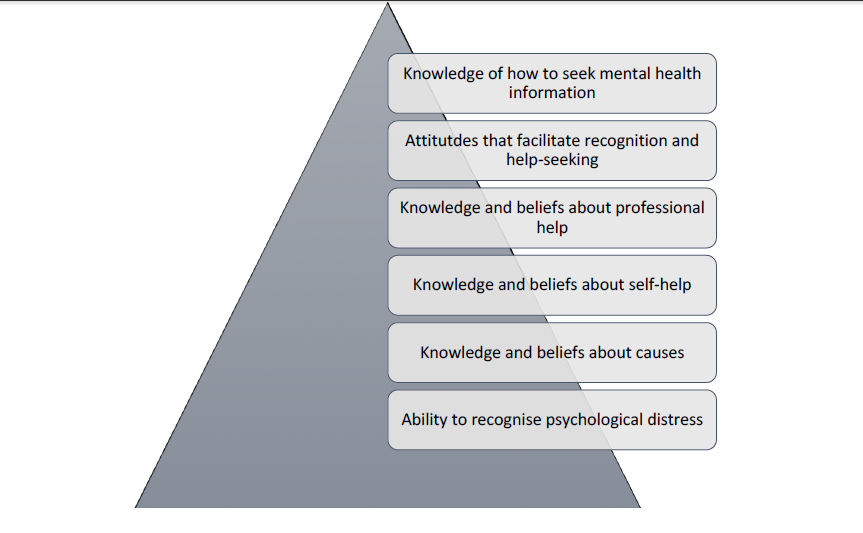

Jorm (2000) as cited in Srivastava, Chatterjee and Bhat (2016) provide a pyramidical model of the components of mental health literacy:

Addressing each of these components, with well-planned and informed lessons is the need of the hour.

Ramalingam and Nath (2012) indicated an increase in the number of suicides and related mental health disorders among school students, bringing to spot light the need for a school psychologist unlike what has been prescribed by CBSE. The CBSE affiliation by-laws state that, the person appointed as Counsellor and wellness teacher shall be either a Graduate/Post Graduate in psychology or child development or a Diploma holder in Career Guidance and Counselling. In most of the cases the counsellors end up being the diploma holders because the graduates are preoccupied with clinical work. So, promoting school psychology as a field in India is really important. Partnerships with different organisations especially Non-Governmental Organisations in the field of education to take such initiatives to the rural areas can help. Kapur (1997) has written a book on Mental Health in Indian Schools where she has detailed about the collaboration with other organizations. Even Nayar (2012) describes the roles of NGO’s in providing mental health service. Apart from this, MANODARPAN can focus on developing its handbook into an extensive curriculum that is age or stage specific. Only if all three aspects (requirement of professionals, partnership with NGO’s and mental Health curriculum) are simultaneously worked upon, can MANODARPAN become successful. Turning MANODARPAN into a comprehensive policy will make the process more effectual. More than making it effectual, it will help in addressing the dearth of policies about the mental health of children in general and specifically in the field of education. This will make the educational activity more holistic, addressing mental health treatment gaps in India.

We at metamorphosis provide need-based, evidence-based, age specific modules on various topics related to Mental Health for free. Reach out to us, for obtaining these modules.

References

Dhankar, R. (n.d.). From classroom to aims: Mapping the field of curriculum.

Manodarpan. (n.d.). Retrieved December 14, 2021, from http://manodarpan.mhrd.gov.in/

Mental Health and Wellbeing – A Perspective. (2020). New Delhi: Central Board of

Secondary Education.

National Education Policy (2020). Government of India. Retrieved from https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf

Nayar, U. S. (2012). Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in Contemporary India. In

S. Das (Ed.), Child and Adolescent Mental Health (pp. 337-350). New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Ramalingam, P., & Nath, Y. (2012). School Psychology in India: A Vision for the Future.

Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 38(1), 22-33.

Srivastava, K., Chatterjee, K., & Bhat, P. (2016). Mental health awareness: The Indian

scenario. Retrieved February 14, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5479084/

Stop Stigma: 12 Inspiring Quotes About Mental Health. (2019, April 29). Retrieved

February 14, 2021, from https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/stop-stigma-12-inspiringquotes-about-mental-health-0512187